The Asian-American community is under attack and, for those working within the fashion industry, turning a blind eye is not an option.

Within the course of nearly 1 year, a harrowing 3,800 cases of racially motivated hate crimes against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community has been reported to plague countless states, with 503 incidents taking place in 2021 alone. According to the Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council, the anti-China rhetoric spans from verbal harassment to physical assault to violent terrorism, all of which are exacerbated by the discriminatory scapegoating of China for the spread of the Covid-19 virus.

As we take steps to lend our support and platforms to combat these unspeakable crimes, it’s important to look back and understand how dominating institutions like the fashion industry have contributed to the orientalist narrative and what we can do to take a stand now.

The emergence of Asian markets has been branded as the world’s most lucrative destination for luxury and aspirational labels, with more than half of global luxury patronage coming from East and South East Asian customers. As designers and models of Asian descent continue to dominate the diversity pool, it may seem that the fashion industry has painted itself the perfect picture of cultural variety. In reality, the sartorial scene still rears its dark underbelly through thinly disguised micro-aggressions that, cumulatively, contribute to a long-standing history of xenophobia.

In the past, luxury houses have perpetuated orientalist behavior towards the AAPI community through a slew of subtle yet equally discriminatory hits.

In 2017, Chanel and photographer Billy Kidd came under fire for an Interview Magazine photoshoot that was said to aggravate culturally insensitive stereotypes. The editorial entitled “CoCo Served Hot” featured an Asian model walking the streets of New York City’s Chinatown carrying a bindle stick full of counterfeit goods. The model is decked out in a Chanel themed conical straw hat, pair of leather gloves, and rope sandals. With a towel draped over her shoulder, it’s clear that the model was meant to look like a gentrified version of a Chinese street-side vendor. The Asian community was infuriated by the tasteless photo series, criticizing it for reinforcing the “hawking and stealing” stereotype that immigrants have worked hard to release themselves from for years. Designer Philip Lim openly spoke against the editorial, calling it an inaccurate depiction of mainland Chinese workers and a mockery of the immigrant struggle. While Kidd defended his work as an homage to the Chinese working class, many saw it as an uneducated jab at the plights of immigrants doing what they need to survive.

In 2018, Dolce & Gabbana launched their D&G Loves China campaign through a series of of short-length episodes called “Eating With Chopsticks”. In each of the three commercials, a Chinese model is given a plate of supersized Italian delicacies that she struggles to handle using her chopsticks. The ads are laden with racist stereotypes, presenting the woman as too uneducated and naive to understand how to adapt her cultural dining practices in a European setting. She’s decked out in a sparkly court neckline dress and gaudy gold jewelry (instead of her own traditional attire) in the middle of what looks to be a traditional Asian restaurant, where she fumbles and fusses with her chopsticks to eat Western meals that are obviously not meant to be eaten with such utensils. It’s the image of a European-embracing Asian who just can’t seem to understand basic table practices. Throughout the videos, a narrator from the D&G team instructs her with chiding remarks on how to use the chopsticks properly. The ads quickly sparked outrage within the Asian community, many disgusted by the blatant mockery of their culture and the grotesque superiority complex the Italian brand expressed to feel they were in the position to teach an Asian woman how to use chopsticks.

Campaign scandals aside, the fashion industry has also been guilty of the commodification of traditional Asian garments in an age-old story of cultural appreciation turned cultural appropriation. Both luxury labels and fast fashion brands have had a history of throwing together and reducing different facets of various Asian cultures to the outdated “oriental” title.

Too many times designers have washed over the rich heritage attached to their motifs, making no distinction between designs of, let’s say, Chinese or Japanese descent. A clear example of this would be Little Mix’s 2019 Pretty Little Thing Collection that came under fire for allegedly encouraging exoticism with a set of flashy “oriental” print outfits that were marketed to “channel eastern vibes”. The Australian brand also failed to cast Asian models for the catalogue photoshoot, all the more sparking outrage from online critics.

Fellow Aussie label Réalisation Par also found itself in a similar controversy over their Emilie Shanghai Nights dress in 2017 and its (now deleted) problematic product description: “We couldn’t ring in the new year without creating a tribute dress to the Far East and all the wild times we’ve had there. From Shanghai to Tokyo, we have had some of the most fun and the worst hangovers but always the best memories.”.

Here we see yet another “it-girl” brand lumping the entirety of Asian culture into one big exotic and monolithic body under the guise of “Far Eastern” patronage. When designers use cultural borrowing to “pay homage”, it begs the question of how anyone can celebrate a culture they refuse to even acknowledge. Cultural adaptation can be highly unethical and detrimental if designers do nothing to empower or be educated about the history they borrow from, making minorities sideline characters to their own tradition. (God forbid they use actual Chinese models for Chinese-inspired clothing, right?) This pushes them into the background and reinforces typecast images of the “passive and subordinate Asian” who will sit in silence as Western figures take the wheel.

And sadly, the list of fashion’s sins against the Asian community does not stop there.

The fetishization of cultural elements has long since stood at the top of fashion’s many other offenses. Case in point: The qipao.

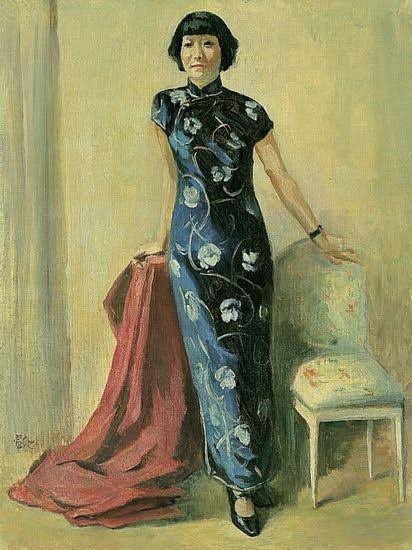

The qipao/cheongsam is a Manchu-originating dress that stands as a symbol of women’s liberation in China, as it was donned by the first generation of empowered and educated women in the 1920s who traded in the hanfu (long silk robes) for a more functional attire. The original design features a high collar, three-fourths sleeves, and an ankle length skirt— a structure that is completely representative of their conservative values.

Today, modernized versions of the cheongsam prefer high slits, short skirts, low necklines, and crop tops. Many might argue that to bound the qipao to perpetually preserve its original form robs designers of creative liberties, but it’s important to note that “modern” variants often reinforce the dangerous narrative of fetishization that the Asian community has had to deal with for decades.

We cannot separate a call for modernization from the fact that Asian women struggle with being seen as hypersexualized and submissive all their lives, making them even more vulnerable to harassment and hate crimes fueled by the “model minority” mindset (the notion that they are the ideal immigrants because they are docile and submissive). While there is nothing wrong with encouraging a progressive and 21st century take on traditional clothing, we must be careful not to encourage 21st century inequalities too.

As fashion stands at the forefront of big statements, we must band together in unison with the AAPI community in fighting against discrimination and injustice. Asian fashion is always culturally rooted, and to separate the history and implications that come with their clothing means to ignore the barriers that both today’s people and their ancestors faced in relation to them. This pushes the community’s struggle to fight discrimination multiple steps backwards when big brands only use their powerful platforms to lay claim to the good sides of a minority’s culture instead of acting as an ally to every aspect of it.

Simply put, you cannot love a culture only for the parts that are easy on the eyes, then ignore the parts that are hard to talk about.

If you are not part of the AAPI community or are simply privileged enough to talk about this topic without having to look over your shoulder the next time you leave the house, start the conversation and be the voice for those who do not have the safety to speak. Allyship is not just about making grand or revolutionary acts, but ensuring that you actively contribute to dismantling discriminatory rhetorics through your everyday actions. Whether you’re a small business owner, a designer, a magazine writer, or even just a casual shopper, you are a bonafide member of the fashion industry, and thus, have the power to change it.

Your support is your best-selling product, and every brand has you on their wishlist.

Give your patronage to brands who don’t reduce Asian culture to caricatures of kung fu or nail salons. Diversify your core teams to include their voices. Treat their traditional clothing as historical gems, not costumes. Veer away from marketing tactics that embedd internalized racism. Boycott chain stores that exploit sweatshop workers. Protect Asian creatives.

The list goes on, but only so that one day the stigma won’t.

For more information on how to help, click here for a list of anti-Asian violence resources.

Sources:

Daily Mail, Jing Daily, The Fashion Law, Fast Company, Asian Pacific Policy and Council, NBC News, Huffington Post, Barron News, Shanghai.ist, and Teen Vogue